Don Hahn remembers dancing corndogs.

Not the food itself, but the image: a cartoon advertisement projected onto a drive-in movie screen, animated hot dogs in their little breaded jackets, twirling under the stars. He was a kid in pajamas, sitting in the back of his family’s Rambler station wagon, and something about those dancing corndogs mesmerized him.

Pure wonder.

No one was measuring his capacity for wonder or asking him to demonstrate curiosity at the appropriate developmental level. He was just present to it.

Somewhere between that moment and adulthood, most of us lose permission to see this way. We learn that creativity is something special, something reserved for certain people with certain titles doing certain kinds of work. We build systems that tell us who gets to create and who doesn’t, who’s ready and who needs more time, whose ideas matter and whose should wait their turn.

But here’s what I want to argue: creativity isn’t granted by titles or performance reviews. It’s inherent. It’s the way you think, the way you solve problems, the way you express ideas that only you could express that way. The challenge isn’t becoming creative. It’s remembering that you already are, despite everything designed to make you forget.

The Myth of the Creative Class

We’ve built a false binary in how we talk about work. On one side: the “creatives.” These are your designers, your writers, your art directors, the people who went to art school and whose job descriptions include words like “innovative” and “visionary.” On the other side: everyone else. The engineers, the analysts, the project managers, the operations people. The ones doing “the real work.”

This division is corporate taxonomy, not truth. It’s a convenience for org charts, not a reflection of how human minds actually work.

Because here’s what gets missed: creativity isn’t a job function. It’s not even really about making art. Creativity is problem-solving. It’s reframing. It’s seeing connections others don’t see and expressing ideas in ways that make people understand something they couldn’t grasp before.

The accountant who restructures a spreadsheet so the patterns finally become visible? That’s creative. The teacher who finds the exact right metaphor that makes calculus suddenly click for a struggling student? Creative. The developer who sees an elegant solution everyone else missed because they were too close to the conventional approach? Creative. The parent who invents a bedtime story on the spot, weaving in details from their kid’s day to make them feel seen? Deeply creative. These aren’t “sort of” creative or “creative in their own way.” They’re creative, full stop. They require the same mental flexibility, the same willingness to see things freshly, the same courage to try something that might not work.

But we’ve organized work in a way that makes this invisible. If your job title doesn’t have “creative” in it, your creativity doesn’t count. It’s not celebrated, not developed, sometimes not even acknowledged. You become the function you perform rather than the mind doing the performing.

The Ladder and the Carrot

It gets worse. Because even within these categories, we’ve built another layer of boxes.

You’re not just an engineer. You’re a junior engineer, a mid-level engineer, a senior engineer, a staff engineer, a principal engineer. Each title comes with its own invisible fence, marking the boundaries of what you’re allowed to think about, what problems are yours to solve, what contributions are appropriate for your level.

Junior developers stick to their tickets. Mid-levels own features. Seniors architect systems. Principals set direction. These divisions feel natural after a while, like organizational physics. But they’re not. They’re arbitrary lines we drew and then forgot we drew them.

And here’s what makes it insidious: the ladder comes with a promise. Do your job well enough, demonstrate the right competencies, show the right growth, and you’ll move up. The next title awaits. More responsibility, more impact, more money, more respect.

The carrot dangles. But the carrot moves.

You get close and suddenly you’re missing something. Not quite demonstrating enough leadership presence. Need to work on your communication skills. Should show more strategic thinking. The feedback is always vague enough to be inarguable and specific enough to sting. You internalize it. You work on it. You try to become whatever shape the system demands. And here’s what years of experience actually teach you, the thing no one puts in the job description: the best laid plans fall apart. The elegant architecture you stayed up until 2 AM designing gets thrown out in a meeting because someone senior had a different opinion. The strategy you carefully researched turns out to be wrong. The approach you were certain about doesn’t work.

What you gain from experience isn’t the ability to make better plans. It’s the ability to think on your feet when plans collapse. To adapt. To improvise. To sit with doubt and keep moving anyway. To be wrong and recover. To say “I don’t know” and figure it out.

This is where real creativity lives. In the messy, improvisational, uncertain space where you’re making it up as you go because the situation demands something that doesn’t exist in the playbook.

But the system can’t measure that. You can’t put “thinks well while drowning in doubt” on a competency matrix. So instead we measure proxies: tickets closed, lines of code, meetings attended, the confidence with which you present ideas regardless of whether they’re any good.

The ladder isn’t measuring creativity. It’s measuring performance of certainty. And those are often opposite things.

The Arbiters Among Us

The hardest part isn’t the system itself. Systems are abstract, faceless.

The hardest part is when the system speaks through people you thought were on your side.

A colleague tells you that you don’t meet certain standards. That you need to develop your communication skills, your technical depth, your leadership presence. They frame it as helpful. Constructive feedback. They’re invested in your growth.

But here’s what’s often actually happening: they’re reinforcing the hierarchy that benefits them. They’re using their position to judge your worth, your readiness, your value. And the criteria they use, especially for “soft skills,” are subjective enough to mean whatever they need them to mean.

Sometimes they’re doing this consciously. More often, they’re not.

They’re proving their own worth by being the one who evaluates. They’re managing their own doubt about whether they deserve their position by ensuring you stay in yours a little longer. They’re scared too, worried they’re not showing up the way they should, and your growth feels like a threat to their standing.

Or maybe you’ve been told, directly or through carefully coded feedback, to care less. To not be so invested. To stop overthinking it. To just ship it and move on.

This advice often comes dressed as wisdom: “Don’t burn yourself out.” “It’s just a job.” “You’re too close to it.”

But here’s what it really means: your care is exposing how little everyone else cares. Your standards are highlighting how much we’ve all compromised. Your creativity is a mirror showing us what we’ve given up.

The person telling you to care less isn’t protecting you. They’re protecting themselves from the discomfort of your effort, from the comparison, from remembering when they cared too much.

Have you ever told someone to care less?

Maybe you were genuinely worried about their burnout. Or maybe, and be honest, their intensity made you uncomfortable. Made you question your own investment. Made you feel like you weren’t doing enough.

Have you ever moved the goalposts on someone? Withheld recognition because you weren’t sure of your own standing? Used “just being honest” as cover for reinforcing your position in the hierarchy?

This isn’t about blame. It’s about seeing the pattern. The system turns care into a competition, then punishes whoever cares most. It turns evaluation into a tool for maintaining position. And we all participate, because not playing feels more dangerous than playing badly.

Here’s the painful truth we all know but rarely say out loud: we’re all figuring this out. The senior IC who can’t code anymore but evaluates others on their technical skills. The thought leader recycling the same ideas in different slide decks. The promotion criteria that reward visibility over substance, confidence over competence.

We know the emperor has no clothes. And yet we keep score anyway, because the alternative, admitting that none of us have it figured out and we’re all just doing our best, feels too vulnerable. Too risky. So we maintain the fiction. We perform certainty. We judge each other by standards we’re not sure we believe in, and we do it because the system demands participants.

The arbiters aren’t villains. They’re trapped too. The person evaluating you is being evaluated by someone else, carrying their own doubts, performing their own certainty, wondering if they’re enough. The whole chain is humans measuring each other by metrics that don’t capture what actually matters, and everyone’s exhausted from pretending otherwise.

What Shines Through Anyway

And yet.

Despite all this machinery, despite the titles and the rubrics and the performance reviews and the colleagues telling you what you lack, something persists.

Your essential truth. The way you think about problems. The connections you see that others don’t. The particular angle from which you approach the world. The way you express ideas that makes people suddenly understand. The care you bring even when you’re told it’s too much.

That’s yours. It doesn’t need permission. It doesn’t wait for a promotion to exist. Sometimes someone sees it. Not always the person with the title or the authority. Sometimes it’s a peer who gets what you were trying to do. Sometimes it’s someone junior who asks you questions that reveal they’re paying attention.

Sometimes it’s a moment in a meeting where your “dumb question” changes the entire direction because you were willing to voice what everyone was thinking but no one wanted to say. Sometimes it’s you, finally, recognizing yourself. The code review where someone actually understands what you were trying to do, not just what you did. The meeting where your perspective shifts how people think about the problem. The moment someone messages you days later: “I’ve been thinking about what you said.” The junior developer who tells you that you helped them see they could do this work, not because you taught them syntax but because you treated their ideas like they mattered.

These moments don’t show up on performance reviews. They don’t accelerate your promotion timeline. But they’re real. They’re evidence that the thing that makes you who you are is getting through despite the system’s best efforts to standardize you.

Permission You Don’t Need to Ask For

Creativity isn’t lightning in a bottle. It’s not something you cultivate over decades until you’ve finally earned the right to call yourself creative. Those things can be true, but they’re not the whole truth.

Creativity is also: showing up and trying something. Questioning the obvious approach. Expressing yourself in a way only you could. Caring enough to do it well. Seeing the problem from an angle that’s native to how your particular brain works.

You’ve been doing this all along. The system just told you it didn’t count because it wasn’t in the right format or coming from the right level or directed at the right kind of problem.

So here’s the question: what if you stopped waiting for someone to tell you you’re ready?

What if you recognized that the doubt, the improvisation, the unique way you see things, that’s not a bug in your professional development. It’s the whole point.

What if the most creative thing you can do is see yourself clearly despite the noise?

That doesn’t mean ignoring feedback or pretending hierarchy doesn’t exist. You still have a mortgage. You still have a manager who controls your rating. You still have to navigate the system because opting out entirely isn’t possible for most of us.

But within that system, you have more agency than you think.

You can find one person who sees you and build quietly with them. You can document your own growth outside the rubric, noticing what you’re learning that the competency matrix doesn’t capture. You can recognize creativity in others, especially those the system ignores, and tell them what you see.

You can use whatever privilege or seniority you have to shield someone else from the worst of it, to advocate for them in rooms they’re not in, to refuse to be an arbiter even when the system asks you to be one.

You can keep caring. Not to the point of self-destruction--that serves no one. But enough to let your work mean something. Enough to let your unique way of seeing problems shine through.

Because the people who told you to care less? Deep down, they wish they still could.

The Real Creative Act

Don Hahn’s dancing corndogs weren’t high art. They were a cheap advertisement for the concession stand at a drive-in theater. But they stuck with him for decades because of the way they made him feel: full of wonder, full of possibility, present to the moment in a way that didn’t require justification or permission.

That capacity for wonder--you still have it.

You just forgot you didn’t need permission to access it.

The most creative act isn’t making the perfect thing or reaching the right title or finally proving you deserve to be called creative. It’s simpler than that.

It’s seeing the systems for what they are: organizational convenience, not natural law. It’s finding the people who are figuring it out alongside you, titles be damned. It’s recognizing that we’re all carrying doubt, all improvising, all trying to bring something of ourselves to work that matters, and that shared humanity is more real than any hierarchy.

It’s remembering that the thing you bring, the way you see, the care you put into your work even when no one asked for it, that’s not something the system granted you. It’s not something anyone can take away.

You were always creative. You just needed permission to remember.

And here's the truth: you never needed permission at all.

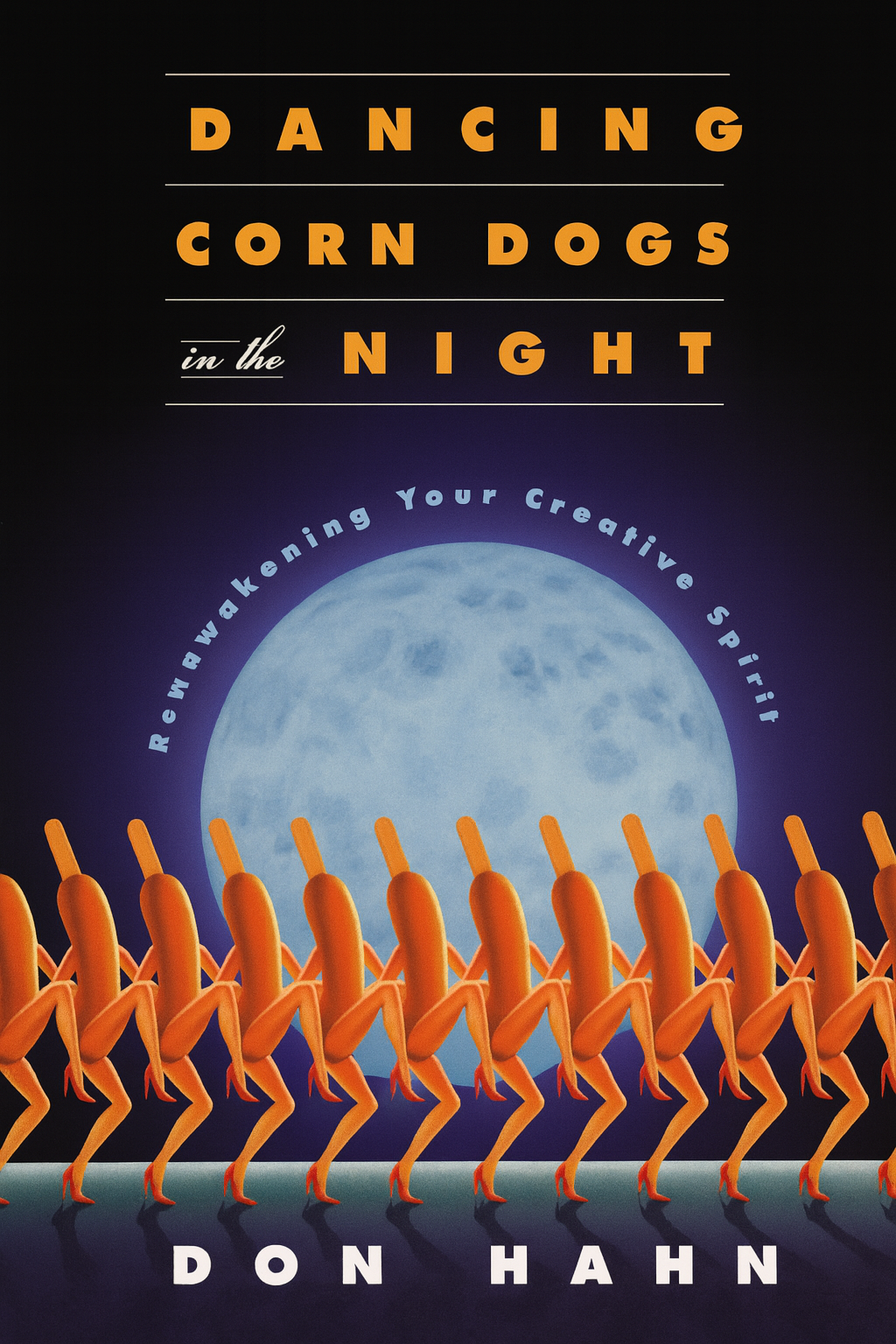

If you enjoyed some of what I've shared here (or all of it), be sure to pick up a copy of Don Hahn's book Dancing Corndogs in the Night.